The secret link between Raymond Chandler and PG Wodehouse ‹Literary hub

My father, who is 78 years old and lives in Malaysia, lunch once a week with a group of his high school classmates. I am impressed, and not a little envious, that he has a group of friends who are so attached to each other that they meet every week, six decades after their first meeting.

The article continues after advertising

My father’s group reminds me of the legendary collection of British novelists and criticisms – Martin Amis, Christopher Hitchens, Julian Barnes, Salman Rushdie and al—Who had a lunch standing for many years. There were of course a few points of difference between these two groups, in particular that my father is teetotal and that the writers by most of the accounts drank as much as they ate … What it had to be to sit on this table – and to prevent us later.

The most productive literary lunch of all time was actually a dinner, and it took place at the Langham hotel in London in 1889, when the publisher JM Stoddart invited two young writers whom he courted to create something original for his magazine, Lippincott monthly.

The written writers were Oscar Wilde and Arthur Conan Doyle and, at the end of what one can only imagine was a fairly fabulous meal, Wilde had promised to write The image of Dorian Gray And Conan Doyle had committed to writing The sign of the four, With a Sherlock Holmes, for the magazine. We hope that no one has questioned the STODDART expenses.

Often, I find myself dreaming of being invited to one of these lunches, or perhaps being present in this motel room in Miami a hot night in February 1964 when Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Sam Cooke drank and spoke in the morning after Ali’s victory over Sonny Liston. I find it unbearably romantic, this idea of a group of great historical characters who are also friends, who have lunch and achieve greatness and who remain the best criticisms and the wisest advisers throughout their lives.

I find it unbearably romantic, this idea of a group of great historical characters who are also friends, who have lunch and achieve greatness and who remain the best criticisms and the wisest advisers throughout their lives.

I suspect that I am obsessed with stories of this type because with my career Zig Zag between books, theater, television and film, I have never settled in a discipline long enough to acquire a very knitted group of peers.

While I have the chance to count many writers of distinction among my friendship group, and even more lucky to have collaborated with many of them, few of my nearest creative relationships could strictly be called peers.

From Douglas Adams (which I met for the first time when I was 18) and David Baddiel to Lenny Henry and Sanjeev Bhaskar, I always seem to surround myself with mentor collaborators, a decade or two my elder, and rather more famous than me.

These last three constitute a coterie of multiethnic national treasures of pioneers, which I admired in adolescence, and which ended up collaborating with the adult. Uplining, I learned from these big ones so much that everything I could lose in peers, I gain in expertise.

In addition, they usually pay for lunch.

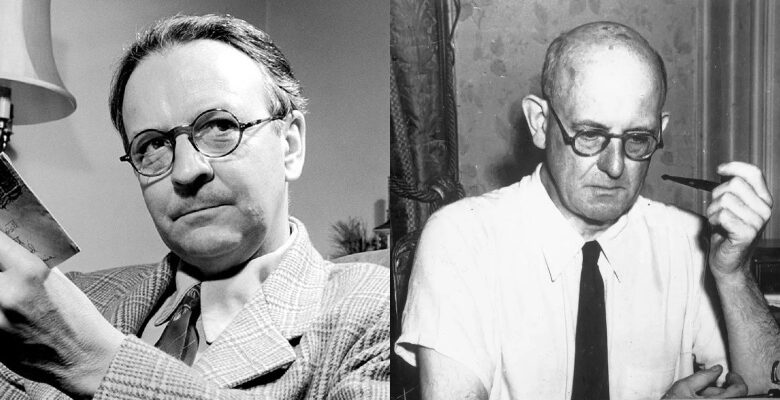

Recently, I seem to take this trend to mine to the extreme, in search of mentoring not only of talented life, but also of The Great Dead. In the past year, I was plunged into the adaptation of two of the best prose stylists of the 20th century: Pgwodehouse and Raymond Chandler.

WODEHOUSE, comic strip columnist for the British aristocracy and creator of Jeeves & Bertie Wooster, Lord Emsworth and the inimitable Psmith, is the undisputed king of the English campaign farce; Chandler, creator of the emblematic PI Philip Marlowe, is rightly recognized as the writer who raised the history of detective to the areas of literature.

Questioned by their respective fields to adapt their work for the scene and the screen, I find myself in the terrifying position of having to write a dialogue which can comfortably sit their perfect original sentences.

Consider the following:

“He was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop gives a hole in a stained glass window.

“She seemed to have been poured into her clothes and forgot to say” when “.

“He had the appearance of the one who had drank the cup of life and found a died scarab at the bottom.

“He seemed as discreet as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.”

“At thirty feet from there, she looked like a lot of class. From ten feet distance, she looked like something invented to be seen from thirty feet from a distance.

“She had a kind of penetrating laughter. A bit like a train that goes to a tunnel.

Hang on. What’s going on here, you might ask? Half of these lines are wodehouse and half are chandler. However, if you can correctly match the right sentence with the right author on everything above, without using the Internet, a) you lie and b) I would like to hire you as a chief editor of script.

It started to become clear for me that these two apparently very different writers have, at least, a lot in common. The two are masters of the unexpected comparison and the heroic metaphor, and the two lacked epithets transferred with a precision similar to a snake: their writings are full of meditative cigarettes, reflected forks, breakfasts and lonely feet that take steps in the right direction but do not go far enough. They share a deep feeling for the rhythm of dialogue, the musicality of words, and neither is afraid of a composed sentence, full of sentences in parentheses and subordinate clauses which pass from high thought to a low gag.

As I climb more deeply in their work, it has become clear that they shared another similarity: they each wrote what are essentially variations on a constant theme.

In each story of Chandler, you have one (invariably blond) Femme fatale, A corrupt millionaire, a blackmail bench, a gangster which, despite its ruthless cream, is also capable of a kind of love, an unreliable customer, a little missing and detective with square jaws to adjust everything.

In each of Wodehouse’s adventures, there is a combination of: an inept baccalaureate, an attractive blond (or brunette, or red), a dominant aunt, a case of erroneous identity and a butler / secretary / secretary / godfather / best friend to settle everything.

Some criticisms say that their repeated and strict use of the formula makes them less artists. It is a shallow and absurd thought. Austen and Shakespeare joined strict formulas; Like of course, Bach and the Beatles – as Douglas Adams said, in a test on Wodehouse:

“It is not important that he writes infinite variations on a theme…. He is the biggest musician in the English language, and exploring the variations in familiar equipment is what musicians do all day.

To say things in another way: a failure always has the same set of pieces and they each obey strict rules, but that does not limit the variety, beauty and endless appeal of the endless games waiting to be played, and Wodehouse and Chandler were both big-masters.

So, how did these two writers become, working in very different genres from different sides of the Atlantic, have such overlap in style and form? It was the mystery that I started to solve. Fortunately, no hard street needed to be crossed, nor tough boys questioned. Google gave me my answer in a few seconds: Chandler and Wodehouse were contemporary at the Dulwich College in southern London. They were classmates.

So, how did these two writers become, working in very different genres from different sides of the Atlantic, have such overlap in style and form?

This news, as you can imagine, has played happily in my fantasies. They were childhood friends! Of course, they were; Perhaps like my father and his friends or as friends & co., they had spent the following decades meeting during lunch and exchanging manuscripts. If this is the case, they were the platonic ideal of my dream, a duo that rises from the court of school to literary domination, together.

More in -depth research and a reality quickly invaded: it turns out that the two overlapped for a brief term, in 1900. There is no report of their meeting or even being aware of each other in school or in their subsequent lives. So much for my fantasy.

I continued to dig, however. The truth, as it is often, turns out to be both simpler and deeper than our imagination. These two great masters may not have learned from each other, but they were both taught by the same teachers.

In Dulwich, seven years apart, they were educated on Latin and Greek by the professor of the classics Phillip Hope and by the director, Ah Gilkes, both men of formidable scholarship and linguistic congratulations. By “educated” read, immersed. Under Gilkes and Hope, the boys copied Virgile and Living by the Court, memorized pages of verse and in freedom, under the threat of the sovereign, until they can each compose as commonly in Latin and Greek as in English.

Later, as the classic Kathleen Riley pointed out, the two writers explicitly recognize this debt; Chandler says: “It seems that a classical education could be a fairly mediocre base to write novels in a hard vernacular language. It turns out that I think the opposite: “While Wodehouse was clear that his schooling” on the classic side … was the best form of education that I could have had as a writer.

As a writer myself who has benefited from the school court to date, great teachers and mentors, the denigration of this story is better than fantasy. It turns out that teachers, it turns out that.

(That Nigel Farage also attended Dulwich, we will consider the exception that proves the rule. It will be lost and forgotten while Marlowe and Jeeves Live Immortal.)

And yet … The romantic in me wants to discover that Plum and Ray were friends after all, that they read everyone’s work and exchanged comparisons and remembered the production of Aristophanes’ Frogs In which they played Tadpole 1 and Tadpole 2. Alas, apart from the Hallucinations of Chatgpt, no evidence of this type seems to exist, but I then remembered the Wodehouse’s own description of his books and where they were seated in the spectrum of literature:

“I believe there are two ways to write novels. One is mine, making a kind of musical without music, and completely ignoring real life; The other is well in life and does not care.

Two ways to write novels, explains Wodehouse. My way and the way to Chandler. Maybe the two old masters knew each other after all.

__________________________

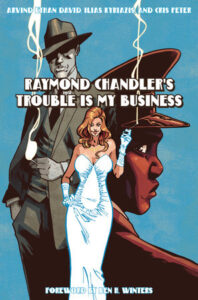

The problem of Raymond Chandler is my companyBY Raymond Chandler And Arvind Ethan David, Illustrated by Ilias Kyriazis, is now available from Pantheon.