Optical illusions that shape fiction – and ourselves ‹Literary center

See is not passive. What we see and how we see him shaping who we are – or at least, who we believe to be – by building, distorting and defining our reality. Fiction knows this well, how our perception is filtered through the eyes we have given ourselves, or those we want to have. But this dynamic is not only a metaphor. It is a psychological, and narrative reality, shaping how the stories are told, understood and even lived.

The article continues after advertising

The best example and the most necessary is the beginnings of Toni Morrison, The most blue eye, in which Pecola Breedlove wants to have blue eyes, just like happy children, blond hair and white skin in the stories she reads. Pecola’s desire follows an innocent heartbreaking logic: blue eyes will make her beautiful, and beauty will make her love, protected and seen. But that also reflects his beliefs in the power of perception. As another character observes: “It was a ugly little girl asking beauty … a little black girl who wanted to get out of the hollow of her darkness and see the world with blue eyes.” For Pecola, the sight dictates perception and perception dictates identity, so that she thinks that changing the way she sees could also change the way she is seen.

What we see and how we see him shaping who we are – or at least, who we believe to be – by building, distorting and defining our reality.

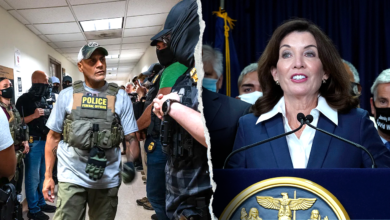

Neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists could agree, to a certain point. The theories of visual perception not only emphasize the way in which sight fails to us, but how these failures shape our sense of reality and self. Take for example “change the blindness” or the well documented phenomenon by which individuals do not notice the unexpected changes in their visual field. In a study, an interviewer asking questions is secretly exchanged with someone else in the middle of the interaction, often without detection. The brain is so focused on the content of the question that it cannot record a visual change. Magicians owe their careers, as they are, to change blindness.

Likewise, the theory of “predictive treatment” suggests that what we see is largely determined by what we to wait for See according to what we be seen. Imagine a small item passes in front of your window. In reality, it was a mutant cicada. But your brain, which draws past experience and probability, see A Robin because Robins is more likely to pass in front of your window than a bizarre insect.

Together, these theories suggest that sight is less to take raw visual data and more on the brain to fill the gaps according to the context and the previous knowledge. The resulting perception will shape the way you see things in the future because, like the story, the vision is shaped by expectations – by what will happen next, depending on what is happening before. The world we “see” is a subconscious construction, a story that our brain builds around us using the raw materials of experience, memory and beliefs. A construction which, in turn, shapes our sense of self.

Go back The most blue eyeWe could then hypothesize that what we, as readers, see – a young girl suffering from trauma, internalized racism and mental illness – is not what Pecola sees. His afflictions shape the very architecture of his perception. And yet, if we can endure an additional tragedy layer, it seems painfully aware of this distortion. She wants to start again with new eyes, eyes that could allow her to perceive and be perceived differently. Eyes that could give him new life.

*

My new novel, His new eyes,, is very interested in the dynamics between sight and identity. Susan, a sixty-eight-year-old woman living in Indiana, receives new eyes. Shortly after, she saw visions of Marilyn Monroe’s life – and gradually transforms, inexplicably, in her. At first, Susan rejects the changes, but as Monroe begins to appear not only in dreams, but in the mirror, the transformation deepens. His body, his conscience and his whole life are starting to move. She becomes someone else. What she sees is what she gets.

If seeing is to believe, literature is an engine of belief – to build and deconstruct the way we see the world.

While Pecola de The most blue eye Pray so that the new eyes lead to a better life, Susan’s new eyes disrupt a life that she was already happy to live. In writing His new eyes, I continually found myself going back to the same question: what does it mean to see the world differently and be seen differently accordingly? This is a question that I believe to be at the heart of the narration.

In literature, sight is not only a motif. It is fundamental on the way we tell and understand stories. The dogma of the creative writing of “Show Don’t Tell” is an obvious example, but it is not specific in the sense of sight itself. Rather consider dramatic irony: in OthelloWe watch Othello unravel because he believes in what he sees – a handkerchief, a glance – but cannot see what we, the public, already know. The tragedy lies in this visual gap, the disconnection between perception and reality, between oneself and the truth. We could apply a reasoning similar to the literary representations of visual deficiencies or blindness. Stripped of a strictly visual entry, the blind dispersed through the desolate novels of Cormac McCarthy are built for themselves a world based on metaphor, abstraction and mystical introspection. And most often, they are considered by those around them as crazy, emphasizing more how the spectrum of sight reflects a spectrum of realities.

Beyond the classic tragedy and the covers cowboys, fiction itself is based deeply on sight-what the characters know, what they are missing and what we, readers, are allowed to see according to history point of viewA term that makes the relationship between narration and sight explicit. For example, Kazuo Ishiguro’s first -person narrators are often shaped by their flashing perception of the world. (To avoid spoilers, I will only say that Never let me go is a masterclass in a character slowly understanding their own reality by bringing together what they have always seen, but never completely recognized). Even in a narrative limited to the third person, as in Elizabeth Strout Olive kitterridgeThe narrator embraces the protagonist so closely that the narrator’s perception – and therefore his voice – presents himself almost indistinguishable from the character. In the second person, the illusion is even tighter: the reader is enlisted in a specific way of seeing the world, a specific self.

If seeing is to believe, literature is an engine of belief – to build and deconstruct the way we see the world. Many has been made of the assertion that reading promotes empathy. But it always looks like a disappointing justification. After all, even sock puppets promote empathy. Reading goes further. This allows us to live in a consciousness not ours. It reconfigures our senses. We try new eyes to better understand ours – we rarely transform ourselves into Marilyn Monroe along the way.

_______________________________

His new eyes By TJ Martinson is available from Clash Books.