My Lai Massacre – Nostalgia Central

March 16, 1968

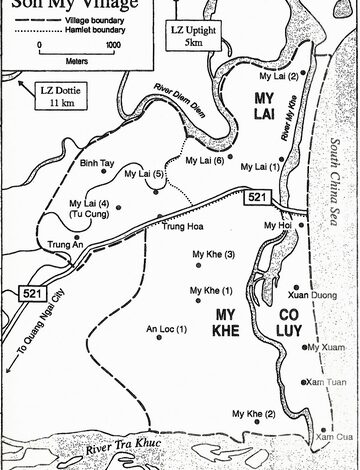

Between 0700 and 1100 a.m. on 16 March 1968, members of “Charlie” Company of the US 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment entered My Lai (pronounced “mee lie”) – a sub-village of Son My village in Quang Ngai. Province, Republic of Vietnam – with orders to find and kill Viet Cong members.

Although the Viet Cong were not found, American soldiers went on a killing spree and were responsible for the mass killing of hundreds (estimates range from 347 to 504) of unarmed Vietnamese civilians—mostly the elderly, women, children, and infants—in one battle. The most horrific incidents of violence against civilians during Vietnam War.

Although the Viet Cong were not found, American soldiers went on a killing spree and were responsible for the mass killing of hundreds (estimates range from 347 to 504) of unarmed Vietnamese civilians—mostly the elderly, women, children, and infants—in one battle. The most horrific incidents of violence against civilians during Vietnam War.

Some women and girls were gang-raped and shot, while soldiers shot or stabbed infants and children using fixed bayonets on their rifles before burning the village.

Villagers who refused to leave their huts were killed by hand grenades.

Harry Stanley, a Charlie Company machine gunner, said during the US Army Criminal Investigation Division investigation that the killings began without warning.

He first noticed a member of 1st Platoon hitting a Vietnamese man with a bayonet. The same soldier then pushed another villager into the well and threw a grenade into the well. Next, he saw fifteen or twenty people, mostly women and children, kneeling around a temple burning incense. They were praying and crying. They were all killed by bullets to the head.

1st Platoon gathered a group of about 80 villagers and drove them to an irrigation ditch east of the settlement. They were then pushed into the trench and shot to death by the soldiers after repeated orders by Second Lieutenant William Calley, who was also shooting. PFC Paul Meadlo testified that he expended several M16 rifle magazines.

Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson of the 123rd Aviation Battalion of the US 23rd Division was flying a helicopter over My Lai when he witnessed American soldiers chasing unarmed Vietnamese civilians.

Thompson located several wounded Vietnamese around the village with smoke grenades and radio calls for medical assistance.

When he returned later, he and his crew noticed that the civilians he identified in smoke had been shot dead. As Thompson hovered over another wounded woman on the ground, he saw an American soldier approach, push the woman with his foot, and then shoot her in the head.

Shocked by this illegal behavior, Thompson landed his helicopter and pleaded with a soldier to help the civilians. The soldier responded that he was “putting them out of their misery” and opened fire on the group moments after Thompson left.

Thompson landed a second time, positioned his helicopter between the fleeing soldiers and civilians and prevented further carnage by ordering his crew – crew chief Glenn Andreotta and gunner Specialist Four Larry Colburn – to train the helicopter’s guns on members of Charlie Company – who were pursuing a group of Vietnamese women, children and elderly people. They order them to shoot the Americans if they refuse his directions to stop the pursuit.

After a tense confrontation with the officer commanding the soldiers – later identified as Second Lieutenant Stephen Brooks – the Americans gave up their pursuit. Calling for help from other nearby helicopters, Thompson (pictured) and his men took the group of fleeing Vietnamese to safety four miles away.

After a tense confrontation with the officer commanding the soldiers – later identified as Second Lieutenant Stephen Brooks – the Americans gave up their pursuit. Calling for help from other nearby helicopters, Thompson (pictured) and his men took the group of fleeing Vietnamese to safety four miles away.

By 11:15, Thompson’s helicopter returned to base. Angered by the morning’s events, Thompson confronted his section commander about the atrocity. By noon, Thompson had reported to the company commander, Major Fred Watke.

Watke stated that he passed the information on to the Cali Battalion Commander but took no further action to report possible war crimes to higher headquarters.

Because of his intervention during the massacre and his subsequent reporting of the events to his superiors, Thompson was ostracized by many of his peers but earned the respect of others.

In March 1998, he was awarded the Soldier’s Medal for bravery and valor. He died on January 6, 2006.

Although Major General Samuel Koster (commander of the American Division) and Colonel Oran Henderson (commander of the 11th Infantry Brigade) received reports that more than 125 civilians had been killed at My Lai—many of them women and children—the two commanders failed to investigate. event correctly.

On April 24, 1968, Henderson falsely informed Koster that “no civilians were grouped together and shot by American soldiers” and that the allegation of a massacre at My Lai was “obviously a Viet Cong propaganda move to discredit the United States in the eyes of the Americans.” Vietnamese people.”

As a result of Henderson’s false report and General Custer’s failure to conduct adequate additional investigations into what happened at My Lai, the incident remained hidden until April 1969, when a former soldier named Ronald L. Ridenhour wrote letters to the White House, the State Department, the Department of Defense, and twenty-three members of Congress describing the crimes. Murder.

As a result of Henderson’s false report and General Custer’s failure to conduct adequate additional investigations into what happened at My Lai, the incident remained hidden until April 1969, when a former soldier named Ronald L. Ridenhour wrote letters to the White House, the State Department, the Department of Defense, and twenty-three members of Congress describing the crimes. Murder.

In fact, the world may never have known about the death and torture inflicted on villagers in My Lai by US forces if it were not for Army photographer Sergeant Ron Haeberle.

After following Charlie Company’s 3rd Platoon into the small village and expecting to document a battle between American guerrillas and Viet Cong guerrillas, Heberly instead ended up chronicling a scene of unspeakable carnage (with his own camera, not the Army’s).

More than a year later, when he returned to his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, he shared some photos of the massacre with the city newspaper, Ordinary traderwhich he published in late November 1969.

A few weeks later, LIFE magazine published a series of Hyperly photos and the full story of what happened halfway around the world last March.

13 officers and enlisted men were charged with “war crimes or crimes against humanity.” Twelve other officers were accused of covering up the My Lai incident, including Major General Koster (whose Distinguished Service Medal was revoked and he was demoted to the permanent rank of Brigadier General), Brigadier General George Young (Coster’s deputy), and Major Watke. (To which Thompson complained).

However, only four officers and two enlisted soldiers were tried, while charges against twelve officers and seven enlisted men were dropped on the grounds of insufficient evidence. In four cases, charges against officers were dropped without investigation.

After this mass slaughter, only one man, 2nd Lieutenant William Calley (pictured below) – who led a platoon to My Lai 4 – was convicted of any crime. He was convicted in March 1971 of the premeditated murder of 22 Vietnamese civilians and initially sentenced to life imprisonment.

He had only spent a few days in prison before President Richard Nixon He ordered his transfer to house arrest. His sentence was eventually reduced to 10 years in prison before he was released on bail and granted parole in 1974.

He had only spent a few days in prison before President Richard Nixon He ordered his transfer to house arrest. His sentence was eventually reduced to 10 years in prison before he was released on bail and granted parole in 1974.

Eventually, Calley, Captain Ernest Medina (his company commander), Captain Eugene Kotok (the battalion’s intelligence officer, accused of cutting off the finger of a VC prisoner during interrogation), and Colonel Oran Henderson (the brigade commander), were brought before a military court. .

Two non-commissioned officers were also tried before general courts-martial: Sergeant David Mitchell and Sergeant Charles Hutto, both accused of shooting unarmed villagers. All of those court-martialed were found not guilty, except Cali.

Lieutenant Colonel Parker, the battalion commander who was perhaps the most culpable officer in the subsequent cover-up of the war crime, was spared court-martial because he was killed in a helicopter crash in June 1968.

William Calley died in July 2024, aged 80. In 2009, he insisted he was “just following orders” in My Lai.

Source link