Man carrying Alzheimer’s gene shows no symptoms at 76, researchers baffle

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

A Washington man seemed destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease — but against genetic odds, he escaped common dementia for decades.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis recently published a study of Doug Whitney, 76, who lives near Seattle.

He has a rare inherited genetic mutation in the presenilin 2 (PSEN2) gene, which virtually guarantees early onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

STUDY REVEALS WHY “SUPER AGERS” MAINTAIN “OUTSTANDING MEMORY” UNTIL THEIR 80S

All members of Whitney’s family who inherited the gene experienced cognitive decline starting in their early 50s or earlier, according to a WashU news release.

Whitney, however, shows no signs of mental decline. WashU researchers wondered whether the reason for one’s continued cognitive health could help protect others from the disease.

Alzheimer’s research participant Doug Whitney seemed destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease – but against genetic odds, he escaped common dementia for decades. (WashU Medicine/Megan Farmer)

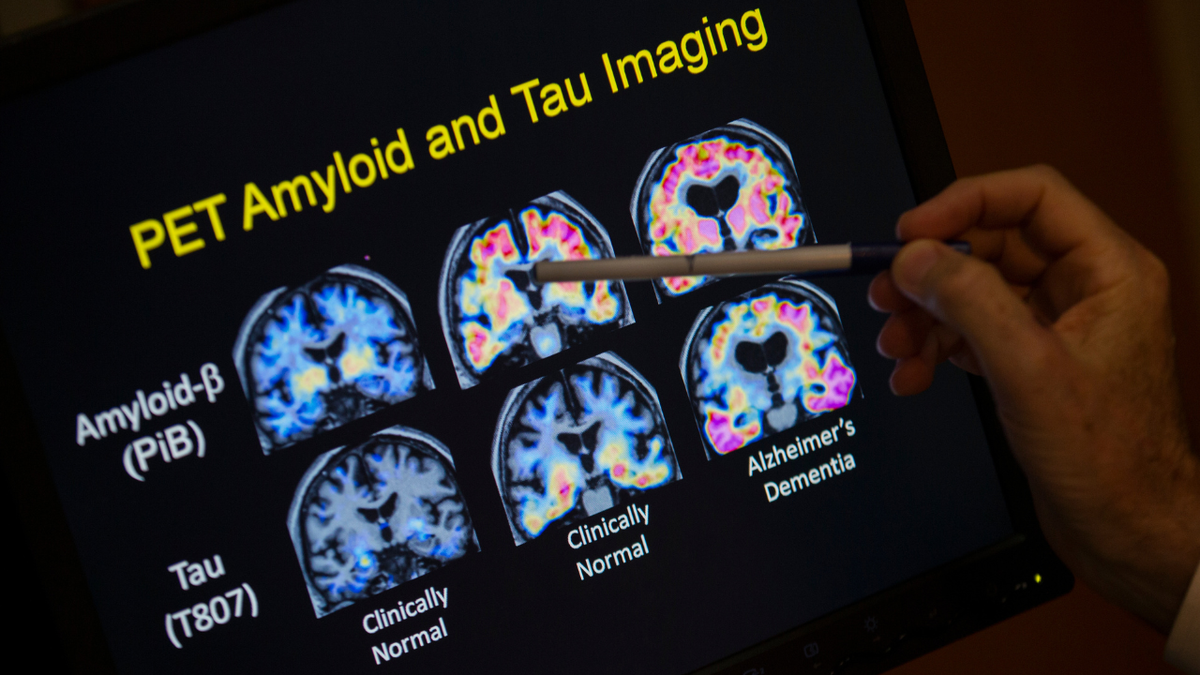

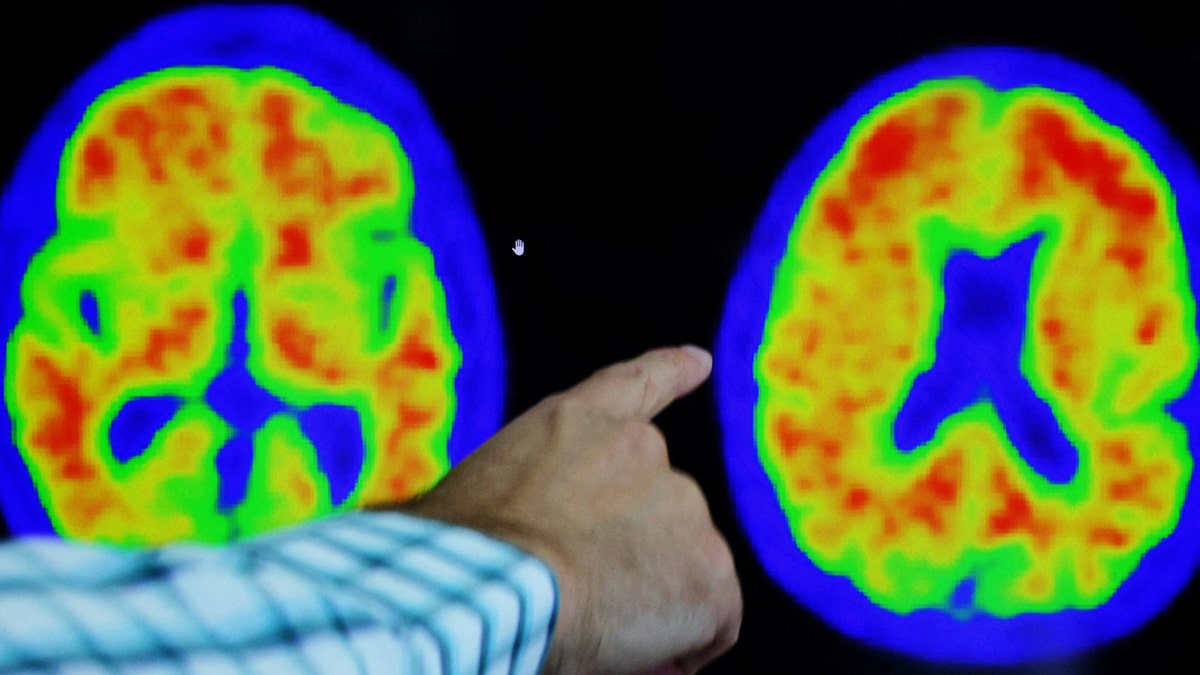

In a study published in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers analyzed his genetic data and brain scans, identifying “changes in genes and proteins” that could explain how he defied the odds to stay mentally sharp.

The researchers also found that Whitney’s brain showed virtually no accumulation of tau, the characteristic protein that signals the start of cognitive decline.

NEW BRAIN MRI PREDICTS RISK OF ALZHEIMER’S YEARS BEFORE SYMPTOMS DEVELOP

“These extensive studies indicate remarkable resistance to tau pathology and neurodegeneration,” said study senior author Randall J. Bateman, MD, Charles F. and Joanne Knight Distinguished Professor of Neurology at WashU Medicine, in the press release.

Urged by her cousin, Whitney first came to WashU in 2011 to participate in a study focused on families with hereditary forms of Alzheimer’s disease, because many of her relatives had developed early-onset disease. At the time, he thought he didn’t have this gene.

“He actually managed to escape the expected course of the disease.”

Whitney’s mother was one of 14 children, nine of whom carried the gene for Alzheimer’s disease. Ten of them died before the age of 60. Whitney’s own brother developed the disease before dying at age 55.

“I was 61 at the time, way past the age where it should have shown up,” he told Fox News Digital in an on-camera interview. “But they tested me, and lo and behold, I had the gene. I was surprised.”

In a study published in the journal Nature Medicine, researchers analyzed Whitney’s genetic data and brain scans. (WashU Medicine/Megan Farmer)

The researchers were just as “confused,” Whitney recalls.

“They tested me three times to make sure there was no slip-up. But it’s true. I had the gene. And now I’m 76 years old and I still have no symptoms.”

Cognitive cues

Jorge Llibre-Guerra, MD, assistant professor of neurology and co-first author of the study, reiterated that it was a “big surprise” to learn that Whitney carried the genetic mutation — officially known as an “exceptionally resilient mutation carrier.”

“He actually managed to escape the expected course of the disease,” he said in the statement.

OMEGA-3 MAY HELP PROTECT WOMEN FROM ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE, New Study Shows

In this most recent study, WashU researchers sought to explore potential reasons for Whitney’s lack of Alzheimer’s disease.

“If we can uncover the mechanism behind this resilience, we could try to replicate it with targeted therapy designed to delay or prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, taking advantage of the same protective factors that prevented Mr. Whitney from developing this disease for the benefit of others,” Llibre-Guerra said.

Doug and Ione Whitney often work on puzzles together to help maintain their mental sharpness. (WashU Medicine/Megan Farmer)

According to the researchers, people with the PSEN2 mutation tend to have an “overproduction” of amyloid protein, which accumulates in the brain during the first stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

During the second stage, when symptoms of cognitive decline appear, there is usually a buildup of tau protein in the brain.

‘Missing link’ to Alzheimer’s disease discovered in human brain tissue study

In Whitney’s case, brain scans showed “significant accumulation” of amyloid, but an almost complete absence of tau.

One theory about how Whitney might have escaped her genetic fate stems from her time in the Navy.

The researchers found that Whitney’s brain (not shown) showed virtually no accumulation of tau, the characteristic protein that signals the start of cognitive decline. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, file)

When researchers analyzed Whitney’s spinal fluid, they discovered a “significantly higher than normal level” of “heat shock” proteins, protective molecules that cells produce when subjected to stress, including exposure to high heat.

During his many years working as a flight engineer in the Navy, Whitney was exposed to high temperatures for extended periods of time.

REDUCED RISK OF DEMENTIA WITH COMMON HEALTH INTERVENTION, STUDY SAY

“In the ships’ engine room, the temperatures…were going from 100 to 110 degrees, for four hours at a time,” he told Fox News Digital. “They concluded that perhaps there was a gene or protein that could mutate and protect me genetically from the disease.”

“We do not yet understand how or if heat shock proteins can mediate this effect,” Llibre-Guerra noted in the release. “However, in this case they might be involved in preventing tau protein aggregation and misfolding, but we are not sure.”

“They tested me three times to make sure there was no slip-up. But it’s true. I had the gene. And now I’m 76 years old and I still have no symptoms,” Whitney said. (Reuters/Brian Snyder/file photo)

The research was funded in part by the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, among others.

“It’s my calling”

To help him stay alert, Whitney often does crosswords and sudoko with his wife.

“I think I’m in pretty good health at 76,” he said. “I’m pretty active and hardly have to take any medications.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

For those experiencing symptoms, Whitney recommends contacting the Alzheimer’s Association.

“Get into research as early as possible: the sooner you get to it, the better your chances,” he said. “Don’t give up. No one is alone anymore. There are many people waiting to help you.”

“Looking at the progress they’ve made over the last 14 years, it’s incredible,” Whitney said. “It is imperative that we continue.” (iStock)

Whitney said he is optimistic about the future of Alzheimer’s treatment.

“Looking at the progress they’ve made over the last 14 years, it’s incredible,” he said. “It is imperative that we continue.”

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Llibre-Guerra said he hopes the information gleaned from Whitney’s case will spark broader studies — in humans and animals — aimed at uncovering the biological secrets behind her resistance to Alzheimer’s disease.

“As long as they need me, I’ll be here. I’m here for the long haul.”

“We made available all the data we had, as well as the tissue samples,” he said. “If researchers would like to ask them to do additional analysis, that is something we would welcome.”

Whitney said he is committed to helping advance Alzheimer’s research, which his wife calls a “third career.”

CLICK HERE FOR MORE HEALTH STORIES

“It became my calling,” he said. “When we go to do tests it’s a pretty rigorous day, but after 14 years I’m used to it now so it’s not a worry.”

“As long as they need me, I’ll be here. I’m here for the long haul.”

Fox News Digital has contacted the researchers for comment.